|

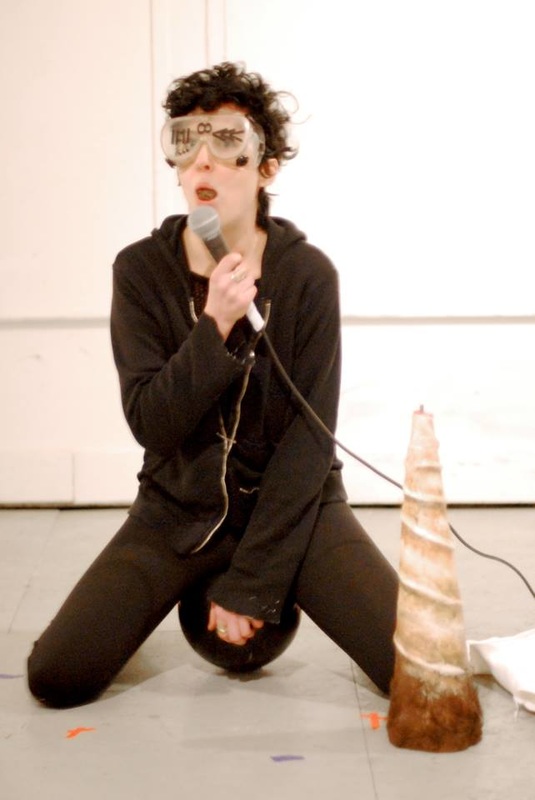

What will we do, and how will we survive doing it? Arahmaiani and Ayana Evans in performance during 21st Century Suffragettes at Grace Exhibition Space. The term “suffragette” was coined in 1903 by London journalist Charles Hands to mock and ridicule members of the Women’s Social and Political Union in the UK. Long since reified, curator Jill McDermid uses the term to conceptualize a contemporary “suffragette” in her Spring performance art series at Grace Exhibition Space and Rosekill Farm, 21st Century Suffragettes. The right to vote is analogized here by a right to perform, to speak, to present viewpoints and personal histories, to effect change regarding the positions and situations of women around the world. Performing on Friday, April 29 at Grace’s famed second-floor loft on Broadway, neither Arahmaiani Feisal (who goes only by Arahmaiani) and Ayana Evans claim to represent all women, or put forward any specific changes to legislature. Instead, their feminist activism is personal, social, and rooted in the political contexts of their embodied lives. Arahmaiani appears initially without costume, without need for a signifying white dress favored by late Edwardian-era European suffragettes and previous performance artists in this series alike. She wears jeans and clogs and walks into the center of the performance space carrying a white candle and meditation bells. Matter-of-factly, she describes her history of persecution and political censorship in and forced expatriation from her home country of Indonesia. She begins by stating simply that she will ask audience members to perform. Because, she says, “in 1983 I was forced to leave my home after being arrested by the military…” As a woman with mixed religious background and as a columnist, artist, and human rights activist, criticism and challenge to fundamentalist Islamist military regimes in Indonesia and Malaysia have left Arahmaiani under attack throughout most of her adult life. She has received death threats (to “drink her blood”) due to her art works "Ëtalase" and "Lingga-Yoni" and her columns and writing about LGBT issues and Buddhism in the newspapers Suara Merdeka ("Voice of Independence") and Kompas have endangered herself and other members of all-women artist groups. Arahmaini has escaped to Sydney, Perth, and Singapore, each time she is attacked refusing to stop criticizing the politicians and corporations that, Arahmaini writes, are usually supporting radical Islamists, using fear and terror to distract people attention from the “real serious problems politically and economically.” Arahmaiani references “morality police” (shariah law enforcers) near the end of her speech and we are reminded of the 2013 proclamation in Lhokseumawe that women must sit side-saddle on motorbikes, since straddling is “sexually suggestive,” “unfeminine” and “un-Islamic.” In this light, Arahmaiani’s casual and “masculine” performance garb make sense and appears to be far more political than it may seem to Western women; instead of bloomers and short-brim round late Edwardian hat, Arahmaiani presents herself partially through her lack of a headscarf, her bare forearms, her powerful gaze coolly pouring into the eyes of the audience members sitting, crouching, and standing in a semi-circle around her. Arahmaiani explains that she needs “help” with her performance; she needs the images and ideas of audience members to demonstrate effective action. She needs solidarity and communality to be able to continue her work emotionally and psychologically. She takes a large plate with the word “FEAR” written in black on it, and carries it slowly towards us, then smashes it against the back wall of the space, where a mandala in impasto layers of earth-toned paint is positioned centrally and lit. After this speech and the smashing of the FEAR plate, Arahmaiani delivers eight white candles individually to audience members. When given a candle, each audience member is expected to perform. After each audience member re-seats themselves, Arahmaiani sounds the prayer bells. The dim lighting and ritualistic nature of this process imbues a sense of gravitas and solemnity to the actions of each audience member. While the duration and manner of action is left completely open, an array of questions seem to emerge: are we expected to express empathy and indignation on behalf of the artist? Are we intending to exorcise our own experiences and emotions? To represent elements of Arahmaiani’s story? Or simply respond somatically with the candle, feeling the situation as if in Arahmaiani’s precise position as a performance artist framed as such and as a 21st century suffragette? AUDIENCE MEMBER PARTICIPANTS | ARAHMAIANI in performance at Grace Exhibition Space | April 2016 | photos courtesy of Miao Jiaxin Two audience members take the opportunity to talk about themselves; one declares herself an artist and describes her own “very well documented” Occupy Wall Street action, which garnered her “hate mail.” We imagine that this story is meant to demonstrate this person’s empathy with Arahmaiani, but her story seems quite petulant and shallow in comparison with Arahmaiani’s experience. Another audience member walks in a circle singing a Buddhist chant and then discusses her recent experience venturing into a Greek Orthodox Christian church and being moved by the priest’s mention of the Madonna and Jesus going to hell before heaven. Recognized by those gathered, one selected audience member is artist Sur, who also paces in the space, marking Grace’s columns before finding a location where he feels “most comfortable.” He then states calmly in a rich voice that he is not hungry, not too cold or too hot, that he feels OK. This action, in its simplicity and suggestion that a focus on the somatic, the present moment, the physical details of existing, seems to respond most directly to Arahmaiani’s request for help in dealing with personal history and political context. The last audience member performer takes his candle deeper into the space, away from the semi-circle, and curls up around it. He remains there for over 20 minutes, before Arahmaiani decides to ring the bells for the last time and signal to Grace Space’s Erik Hokanson to announce that her performance is over. As a whole, Arahmaiani’s performance feels both generous and dangerous. On one hand, she is making space and time for others, gifting her performance to others in order to stage a collective envisioning and multiplicit activity. On the other hand, she surrenders control of the performance, and exposes and implicates other bodies; What would you do? Arahmaiani seems to be asking us. This question is both an honest inquiry and a challenge. Ayana Evans’ performance also seems to operate as both an inquiry and a challenge. The artist is wearing her notorious Catsuit, a skin-tight leotard of fluorescent yellow-green and black zebra stripes, and black high heels. Her comfortable sneakers are left in the center of the space with bunches of white plastic roses and some braided white hair tracks. Arahmaiani’s mandala remains on the wall with the pieces of broken FEAR plate scattered below. Evans proceeds to perform a clear and stable action: 20 jumping jacks inside, then run down the stairs and across Broadway to the other side of the street in front of the Laundromat, perform 20 more jumping jacks, run back, repeat. When Evans goes outside, the audience flocks to Grace’s large windows overlooking the street, looking down on Evans as she looks up at us. She performs this process ten times; the artist is in excellent shape but still becomes more and more exhausted. She seems to be taking the action as a base-state, positing that we must act, that we are moving, acting, no matter what. In order to survive, the question is not what we will do, but how we will survive doing it. Despite this somewhat fatalistic action and its references to women’s labor as an ongoing, exhausting, and undervalued force of resistance and endurance, Evans’ performance attitude—which is also matter-of-fact, friendly, almost casual—encourages a feeling of something like “honorability.” While there are few positive words for such a feeling—“righteousness” seems too selfish and does not connote the bittersweet, teeth-gritted self-determination that can motor activism and prevent an en total slide into helplessness and despair—a certain freedom and exuberance is evoked by Evans’ action. It is not so much self-punishment or surrender to a monolithic fate of oppression that drives her jumping jacks, but rather the ability to “exercise,” to exercise the right to perform, to pursue physical movement of her own choosing, to “improve” the self, no matter how absurd or futile that labor may be judged by others. This is my body and I do what I want with it; Evans invites audience members to run with her, offering to share her challenge, and some do, while others drift into sideline conversation and wander towards the bar. After the jumping jacks, however, Evans gathers and silences the audience easily by standing still for a moment in the center of the space. She then distributes the white plastic roses and bunches of hair around the space before attempting to jump from one to the next. This task is impossible; the items are too far apart. In juxtaposing the two actions, we might interpret the first as a skilled exercise, for which Evans has trained. The first action is something that most people could not do, that Evans has selected and presented to carry a potent array of symbolisms and possible interpretations. The second action might encourage more literal interpretations: the artist failing to reach the white roses and hair tracks no matter how far she jumps. She is unaided by the audience during the second action. Finally, Evans says that she has not yet recovered from the death of Prince, and plays Let’s Go Crazy (1984), encouraging everyone to dance together. This last action reinforces the celebratory feeling of the jumping jacks, perhaps suggesting that even sorrow and loss can motivate perseverance. AYANA EVANS in performance at Grace Exhibition Space | April 2016 | photo courtesy of Miao Jiaxin Both performances do indeed feel like demonstrations. This sense of “demonstration” is at least twofold: in a first, more literal sense of providing an example, both artists demonstrate possibilities for feminist social interaction involving solidarity and collectivity by inviting audience members to perform and participate. Both Evans and Arahmaiani expertly facilitate and muster the mood and atmosphere of their performance situations, while refusing to coerce or control audience member behaviors and interpretations. For both artists, the connective tissue between the personal and the political is social interaction, empathy, and sharing of temporary and ephemeral performance experience. Both artists literally “demonstrate” how such connection and cohesion can occur, via the forms of their interactive performances. In staging the action in binary between the space privatized by willful attendance (the gallery loft) and the public street, Evans further demonstrates how self-determination and artistic performance can bridge personal and political locations, each bleeding into each. Here, a second sense of “demonstration” evokes direct political action. The “dance-ins” of Black Lives Matter and mass memorial services for representative pop stars (such as Prince) are cultural demonstrations, contextualized here in parallel with decades of women’s marches and protests. Similarly, Arahmaiani’s performance takes the form of a public workshop, of the kind that could be held with almost any group of gathered persons as part of a sit-in or teach-in. Any knowledge of the two artists’ related works adds to this distinct bridging of public and private/personal and political; Evans has worn her Catsuit to many artworld events, filming candid reactions to her body and presence and operating as a one-woman protest of white supremacy and misogyny, and is currently performing a project wherein she provides free SAT and ACT tutoring, while Arahmaiani has indeed generated public uproar as she protests and writes about religious sectarianism, gendered laws, economic/environmental extraction, and many other political issues. The literal ability to continue, to self-determine ones own actions and present the self in complex and individual ways is the human right demanded by these feminist performances. For 21st Century suffragettes, there are still laws to be changed, militant police forces to combat (in both Indonesia and the USA), and media attack, body shame, and public ridicule to suffer. Framed and contextualized in an art context at Grace Exhibition Space, both Arahmaiani and Ayana Evans brilliantly condense and articulate their socio-political positions as artists and activists, while inviting each audience member to consider and attend to their own experiences, perspectives, and abilities to keep on going. - Esther Neff, Performance Is Alive Contributer 21st Century Suffragettes continues at Grace Exhibition Space and Rosekill Farm every other Friday: visit www.grace-exhibition-space.com for full information. Works by Arahmaiani are currently featured in the following group exhibitions: Costume National: Contemporary Art from Indonesia, AXENÉO7, Quebec, Canada (through May 5) and Galerie SAWGallery, Ontario, Canada (through May 21); When Things Fall Apart – Critical Voices on the Radar, Trapholt, Kolding, Denmark (through Nov. 28); In & Out of Context, Asia Society Museum, New York, NY, USA (through Jan. 8, 2017). Work by Ayana Evans can be seen live at Panoply Performance Laboratory on Thursday, May 5 and on Saturday, May 21 at FiveMyles. Her free SAT and ACT tutoring project is open to the public every Saturday through May 21. Visit www.ayanaevans.com for more information. ABOUT ESTHER NEFF

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

CONTRIBUTORSIan Deleón Archives

July 2023

|

|

MISSION // Based in Brooklyn, NYC, PERFORMANCE IS ALIVE is an online platform featuring the work and words of current performance art practitioners. Through interviews, reviews, artists features, sponsorship and curatorial projects, we aim to support the performance community while offering an access point to the performance curious.

Performance Is Alive is a fiscally sponsored project of Fractured Atlas, a 501(c)(3) charity. Contributions made payable to Fractured Atlas for the purposes of Performance Is Alive are tax-deductible to the extent permitted by law. |