|

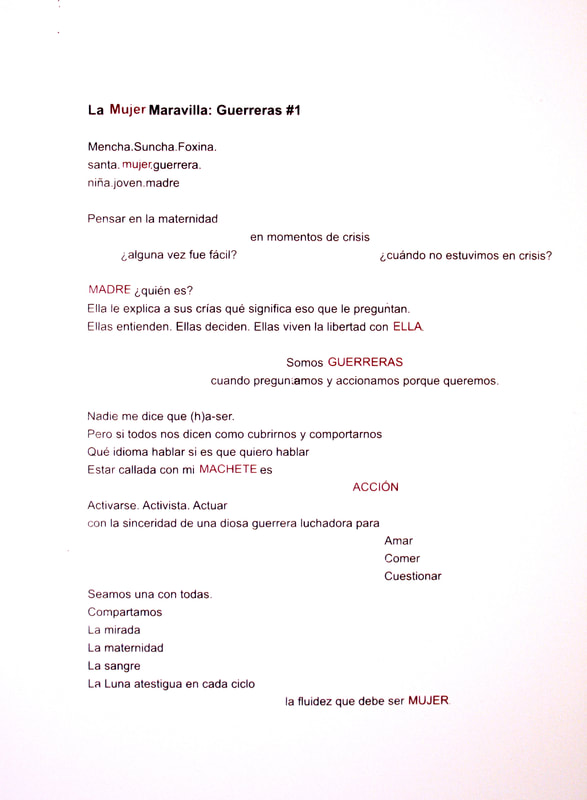

Awilda Rodriguez Lora is a performance choreographer and cultural entrepreneur. Born in Mexico, raised in Puerto Rico, and working in-between North and South America and the Caribbean, Rodríguez Lora's performances traverse multiple geographic histories and realities promoting progressive dialogues regarding hemispheric colonial legacies, and the unstable categories of race, gender, class, and sexuality. Rodríguez Lora has been an invited guest artist at the Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance (BAAD), Brooklyn Museum, New York University, the Art Institute of Chicago, Columbia College Dance Center, University of Michigan and Universidad de Puerto Rico, among others. Rodríguez Lora’s work was recently included in “Comfort Level,” a show at Field Projects Gallery, on view May 3-June 9th, and in “Tool Box” a limited artist’s edition and fundraiser for Agite-Arte, both co-curated by Alissa D. Polan and me, Sarah G. Sharp, and performances at La Mama Theater and the Brooklyn Academy of Music among others. We asked Awilda to create a performance for the “Comfort Level” closing party, La Mujer Maravilla: 4654, which was incredibly moving. I sat down to discuss creating that performance and her creative influences just two days before she performed La Mujer Maravilla: Cuerpa at The Brooklyn Museum, which was part of the Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985 exhibit. SS: Let’s start by talking about the photo and text titled La Mujer Maravilla: Guerreras, that was in “Comfort Level” at Field Projects Gallery. My understanding is that the image and accompanying text resulted from a performance that you did in Puerto Rico? ARL: It’s a performance in a way, but that’s a big question, too, “what is performance?” It was a collaboration that had a performative aspect to it and the documenting of it. I had been talking to Jomary Ortega, who is the performer, the mother and artist in the picture with her children, about how to collaborate together. Her work is also inspired by motherhood. We’ve become interested in each others work and process. This photo and text is our second collaboration and my first photo exhibit. After the May 1st, 2016 Workers March at the Milla de Oro (Financial District) in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Bill 743 was created to be an addendum to the Penal Code. The Bill 743 penalizes wearing ¨Capusha¨, masks or anything covering your face at protests. The bill was approved shortly after the 2018 May Day March by the government of PR. This inspired me to work together with Jomary in creating ¨Capuchas¨ for La Mujer Maravilla: Guerreras. Since returning to Puerto Rico in 2010 I´ve been active as a participant of multiple protest for the independence of Puerto Rico and one can recognize recurring images that become part of them for example: t-shirts that are turned into masks. This domestic item becomes a tool to protect ourselves from police profiling and from the gasses and chemicals that the Police of Puerto Rico as been known as using against protesters. SS: So this law said that you couldn’t cover your face if you were in a protest or in public space? It’s about facial recognition? ARL: The Law penalizes who ever is wearing a mask to avoid being recognized when committing a crime, also penalized if obstructing any private or public entrance and publicly incite any act that is categorized as a crime by the government. I believe this law was created to protect the political and economic interest of the Puerto Rican and Federal Government and not the right to protest that we US citizens have. In my life project, La Mujer Maravilla, nudity is has an important role. Women are also being policed for our breasts. Even breastfeeding is something that we can’t do in public spaces. Being bare chested is sometimes seen as violent by the public. So I was imagining that suddenly all these women were going to protests and they needed to protect their identity, so they take their shirts off and turn them into these masks and then they become warriors.That’s what I imagined, you know, this manada, this group of warrior women ready to fight for social justice. SS: I really like the way you’re expanding iconography that you’ve already been working with. The symbol of the machete, in the hands of a mother wearing a mask she’s made herself, has such an expanded meaning. ARL: Jomary´s daughters questioned me during the process, asking “what’s a machete?” I explained that I chose the machete because it is a tool used to gather food, open paths and also a tool of resistance in Puerto Rico, the Caribbean and America. SS: You mention that motherhood, and caring for people is something that you are interested in. That makes me think about how you began the performance that you did at Field Projects. At the beginning, you appeared in the gallery with a bottle labeled “SUSTENTO” filled with a mysterious liquid. You talked to us a bit about wanting to be a mother, having your own kids biologically, but what it means to give care more universally. Then you asked us to tell you what sustains us and to trust you and take a drink from the bottle. I know you’ve done this sort of action before with SUSTENTO, can you talk a little about that process and how it connects to the rest of your performance? ARL: When I began La Mujer Maravilla, the first thing I thought of was my mother, and I thought about how she gives me SUSTENTO. I want to have a conversation about “What is SUSTENTO for us?” I want us to recognize each other as humans. Working on breaking away from the dichotomy of the two spaces, the performer and the audience, the audience and the performer. I use performance to transform things that affect me, that affect women of color, queers, there is so much charge with that and this can’t be done without having a relationship with the people present. I don’t want them to think we’re invincible. Therefore SUSTENTO allows me to have a conversation about what keeps us alive, because at the end of the day that’s always a question we ask. We’re all trying to push through, to keep doing the things we love, or keep loving, or being there for somebody. SUSTENTO is what keeps us moving. It’s an important ritual that exists with the life project La Mujer Maravilla. It is one of many ways we can connect with each other and all be complicit with the action. SS: It does change the feeling in the room. It seems like it shifts things between you, as the performer, and the viewer. When we enter a gallery space, we have expectations about watching a performance, we’re going to consume, and maybe not participate, and everyone has their own boundaries around that. Field Projects is a small gallery, so people weren’t only revealing what sustains them to you, but to the whole group. Hopefully that prepared a space for your performance. ARL: Yeah, and I think that’s why I do this over and over again, because I feel that as a human species we are very disconnected and sometimes spaces tend to be about the spectator and entertainment or the performance. We can come in, do this thing and then walk away, and that’s it. At least here you’re going to acknowledge someone’s sustenance and learn how we are all connected. As simple of a word as SUSTENTO is, I’m hoping that conversation then supports the performer/witness. If I don’t do it, then I don’t know, something might happen to us. SS: It makes you feel less vulnerable in some ways. Or more protected and then able to be vulnerable. ARL: I am thinking about this now that I’m going to perform La Mujer Maravilla: Cuerpa at the Brooklyn Museum, where people come in to consume objects. I’m a woman of color, and I’m going to take my clothes off, and I’m going to have certain objects in the room, and I’m going to ask them to touch my body, and do things to my body and I’m not ready to do it if I don’t have a conversation beforehand. Others have done it before, you know, Marina Abramovic has done that, Yoko Ono has done that, but we’re living in a different world with communications and networks and social media, these things that connect us also disconnect us. So I’m hoping with SUSTENTO, I won’t be harmed. But it could happen, too. Which is the world we live in, right? Someone called it a social experiment, the SUSTENTO, to see how we feel a little more responsible for the act that is about to happen. SS: I think it’s a very real tension. When you’re talking about what it means to perform and make your body available and vulnerable to a public and how that intersects with histories of colonialism, race, gender, voyeurism and desire, but at the same time, produces witnesses to that horror too. There is potential for actions that are about about provocation that are so unaware. There seems to be more risk in the context of the big public museum vs. the small gallery. You mentioned Yoko Ono, Marina Abramovic. I’m curious, before we talk more specifically about the performance at Field Projects, do you see yourself within a lineage of artists? Do you look broadly at a bunch of different artists and dancers? Are there people who really anchor you? ARL: Well, I came from dance so dance was the only thing I knew about. Chicago is where La Performera was born. I had the opportunity to work with Tim Miller, who is a performance artist from the “NEA Four,” the controversial artists whose NEA funding was removed by congress in 1990. I applied to Links Hall´s Charged Bodies Mentorship Program for Queer Performers, just because I knew of Tim Miller. He was the kind of person I wanted to learn from. He’s also a queer activist. And with him I learned that I was able to do a piece by myself, about my own lived experience as a black latina queer woman. Performance and Performance Art started becoming part of my way of expressing myself. My partner at the time was doing performance studies at Northwestern University, so I was getting these books about performance art and learned about Marina Abramovic, Ana Mendieta, Regina José Galindo, Nao Bustamante, Coco Fusco and many more. Tim also introduce me to other amazing female artists, Carolee Schneemann and Annie Sprinkle. But after Tim and before Tim I’ve had so many great teachers and mentors, my mother being both. The Radical Women exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, to me is the best catalogue of the kind of work we should be reading and looking at. It was very inspiring to see the explorations of different topics and themes: how we deal with violence, sexuality, humor, artists’ self-expression and our self image. But a direct lineage I don’t know, because so many people have influenced me. I have people in Puerto Rico that inspire me as performance artist and dancers, for example Las Nietas de Nonó, Mickey Negrónn, Teresa Hernández, Awilda Sterling Duprey, Jomary Ortega, Ivette Román, Gisela Rosario, Marisol Plard, Nibia Pastrana, Jomary Segarra, La Trinchera, Aravind Adyanthaya and out of Puerto Rico Sharon Bridgeforth, Barak ade Soleil, Antonio Ramos, Larissa Velez Jackson and many others. I am interested in the present and those that anchor me are here creating work and challenging narratives everyday. SS: At Field Projects, you were dressed in all black and wearing shirt that read “I Am Not Exotic, I Am Exhausted.” Can you talk about how you crafted your image and how you worked out the details for this performance? ARL: Well, right now I’m in a state of mourning. Especially after these two hurricanes, Irma and Maria, so black has become a big part of my costume. I’m making it a point to come in dressed in black. ¨I am Not Exotic I am Exhausted” is a quote and response from Morocco artist, Yto Barrada when she was asked in an interview “What is your work without Tangier?” The shirt was a gift from brazilian performance artist Jenny Granado. The shirt encompasses everything I’m feeling right now. Especially how, as an island, Puerto Rico is seen as this really exotic beautiful place, this place where you can grab and consume whatever you want, and then leave. Which is how I sometimes feel my body is being seen, as a caribbean black woman.The mask used in the performance was created with Jomary Ortega. I’ve played with the flag before, as part of my costume. I used gold scissors because Puerto Rico is seen as a “rich port”, and gold is something that has been taken away from us. I braided my hair as its part of my protesting ritual. And then I take my shirt off because the breasts are my armor. “I’m not exotic, I’m exhausted” shirt is placed there because that doesn’t go away. Then I cut the number 4,645 out and then I sew them onto my skirt and then I remove them as the act of how we disappear in the news and in our memories. We forget and we need to constantly remember it is not only the 4,645 deaths in Puerto Rico, it is the history of violence and disaster capitalism that the United States of America has perpetuated onto their citizens and around the world. We have a very complex political and economic relationship with the country, a lot of our schools get paid by federal funding, a lot of our artists get paid by federal funding and you know, this is why we keep these connections as a way for this economic “SUSTENTO”, but then again the US also doesn’t allow the SUSTENTO to come in to Puerto Rico because of the Jones Act. That's neglect! It’s sad and frustrating. When Hurricane Maria happened, I was in New York and I knew about the deaths as I kept learning about it everyday and was so frustrated with the way the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) handled the disaster. I decided to go and visit their offices in New York at the Federal Plaza with a friend who was also feeling the same sadness and frustration. We wanted to get answers. As we look at the building feeling helpless she gets a phone call from her cousin in Puerto Rico who then tells her that they just found her aunt dead in her home. We cried so much right there in front of the Federal Plaza, the building that represents the control of SUSTENTO to US Territories. On October 12, 2017 (Columbus Day) I made a call out to go and give a GRITO (scream) to the entrances of the Federal Plaza. Six of us screamed at three of the entrances. It was great because we were able to release that anger and frustration but, at the same time it made you feel so powerless. That’s a constant feeling I’m trying to understand and performing at the Comfort Level exhibition really activated these emotions and challenged me on the act of doing. I felt really held in that space and very grateful for the opportunity to be able to process in a public space. I am very grateful to have that moment. I needed that, a lot of us needed it. We are not powerless. SS: Going to scream at the entrances of the Federal Building, that action, at its, core connects back, for me, to you ripping those numbers out of your skirt. Initially, you were cutting the numbers 4,654 out of an American flag. As a viewer it took me some time to understand what the numbers represented. We watched you carefully thread the needle over and over again, and sew these numbers onto your skirt and when I realized you were going to tear them all out, it was so poignant... the idea of of disappearing those numbers away, but also this idea of futility, you’re just one person sewing, you’re just one person screaming at this giant building. One of the things that really stuck out to me was how carefully you removed every thread, you had taken so much care to sew the numbers on and now that sewing felt futile. You really stayed with your own timing and pacing. Can you talk a little bit about what it’s like to be in the middle of a performance and stick to the process, see it all the way through? ARL: To be honest, I knew what I wanted to do, but I didn’t know how it was going to happen. I had a certain idea of the images I wanted to create in the performance. In the act of doing I realized, okay I’m going to sew this now, and it’s going to take a while. I bought the thread in Mexico because it’s shiny red and it’s really beautiful, but it’s actually really difficult thread because it’s metallic and it comes apart. Awilda Rodriguez Lora, La Mujer Maravilla: 4654, 2018, 90 min., (1 min. video excerpt.) Field Projects Gallery, NYC. Photo Credit: Jose Santini SS: Yes, I do a lot of work with metallic thread, and I thought about that when I saw the embroidery thread you were using. ARL: I have to breathe in. I have to take my time. I have to believe in the process. It was an exercise in believing in myself. As much as I perform I still get nervous, all the eyes are on you, seeing every little detail, there’s no lighting cue, there is no music to entertain, it’s just me and this task that I’ve just given myself to do and I want to do it well because I am honoring so many of us. I had to do it well, by just taking the time it needs to be done, and in the process of doing I realized how much more it was. Sewing the numbers, and choosing even how clearly I want viewers to see, in what direction do I even put them? Do I arrange them for me to read? Do I arrange them for you to read? All those decisions were made at the moment that I was doing it because it was the first time I’d ever done that action and that’s how I like to create performances now. “Wow, how much do I need to trust myself in this process for it to be as real and honest as it can be?” If I don’t do this with a pure honesty, a simple task can be so complex, I’m not honoring what I’m here to do. It was a constant reminder every time I had to thread the needle. I wanted it to be as smooth and as clean as possible but, then there was all the messiness. I was looking at the threads like, “Ah! It’s not looking as pretty. I know how to sew better than this!” but then I was like, “This is what’s happening Awilda, you have to let it go and just keep doing it, it’s going to come.” and it took its time. I was like “Maybe it’s taking too long?” but then I have to constantly question myself and also taking care of myself in the process. “Ok, Awilda, here you are, do this.” And that, apart from all the other work is also why we do this work. Not thinking in a selfish way, just honoring everybody. Sewing is a beautiful task. All the details of the process, I think that’s what it was really about. It was great. I actually trust myself a lot more now thanks to that performance. SS: Yeah, you begin with setting up your intentions, which are coming from years of experience. You were talking about wearing black to signify being in mourning and you did this performance with sewing. Being the mourner and sewing, as a domestic action but also a marker of time, connects to larger ideas about women’s work. And you’ve talked before about resisting “becoming your mother” but also embracing it. Can you talk a little more about that tension in terms of gender presentation and how you turn the tools of the mother into tools of resistance? ARL: This is why La Mujer Maravilla is a living project, I don’t think it’s ever going to end, even though sometimes I do want it to end. I’m questioning my womanhood a lot. I had a shaved head for years in order to look queer, or not look so much like a woman. Now I let my hair grow, and with that comes a lot of attention and exploring my own femininity and sensuality. That’s what the performance at Brooklyn Museum is dealing with. I take my clothes completely off, full nudity, because there are still not a lot of bodies like mine in museums and galleries and spaces like this or even ads in magazines. I did try so hard to look like those images when I was younger, and that wasn’t a healthy decision. I am also exploring the expectation of nourishment from woman. How do you nourish others and practice self-care? How much can I really give you right now? Because I’m exhausted. What is SUSTENTO for me? I don’t think I know, because I’m exhausted. So I want to have this conversation and see how that transforms in the institutional space of the museum. I have scissors now, I have an American flag, I have gaffer tape, I have a wig, I have lipstick, I have black eyeliner and I ask the audience to construct me with these items. l ask them to come and touch my body and create their Mujer Maravilla. I do poses that recreate images from rape, porn, birth and personal experiences as a woman. By repositioning my body into this images I reconnect to all of the history that my body has gone through. I also make a reference to my age because the audience has 41 seconds to recreate their Mujer Maravilla. I am exploring how we have been sexualized as colonized bodies since 1492. We were raped, and we are still getting raped. We’re black, we’re mestizas, criollas, we are still being raped. How do we close that cycle? We’re getting sexualized and abused because the system, or the media, or colonization promotes the sexual gaze to black and brown bodies. After giving SUSTENTO, how do we see that body that was so nourishing in the beginning, also being very vulnerable, and sexualizing herself for your gaze. Now you look at me, maybe in a very different way and hopefully another young or elder latina black woman will be treated with the love and respect she deserves. SS: There’s an added layer to that kind of performance happening in the context of an art museum. Shows like Radical Women represent women of color with a hopefully more complex “gaze.” You mention the effect of current forms of media, but I also think about images of women of color throughout the history of art, images that are all about this kind of consumptive or voyeuristic gaze. And of course, challenging that is part of what many of the performance artists we discussed have done. Artists who have taken charge and questioned what it means to show your body in that space when you are both the subject and the author, rather than being the passive object of the gaze. Not to mention the way the history of art is intertwined with colonialism. ARL: Yeah, exactly. Thank you for that. SS: What do you see as the next steps? ARL: Well, I’m working on trying to get funding for more collaborative work with the project of La Mujer Maravilla. I actually want to develop a model on how to create La Mujer Maravilla with a collective point of view, hopefully a full evening performance with other female performers. A model where it can be done anywhere by anyone interested in exploring and questioning womanhood. SS: And do you think that will be centered in Puerto Rico? How expansive will your collaborations be? ARL: I want to start in Puerto Rico, since it’s where my heart is right now. I’d love to work with artists there that I admire so much. I would love to be able to have them all in one space and create this work. Then I can take the model created there internationally so it can grow. Our experiences are very different around the world and I want to learn more how Mujeres Maravillas exist in our contemporary times. SS: And when you say women, do you mean self-identified? Is it an open term for you? ARL: Completely. And that’s something I want to explore more. I know it comes with a lot of conflict. We don’t all identify in the same way. Being called a woman doesn’t mean the same thing to me as it does to you, or vice versa. Even the cycles are not the same! So yeah, I’d like to explore that with people who identify as male or female, to see what that means. SS: Is there anything else you want to say? ARL: No, I’m just really grateful for the opportunity that Tool Book and also Comfort Level gave me to show photography, and to do the performance. All of you held that space for me, everybody stayed and held it and I felt really grateful. So gracias, thank you. SS: Thank you!!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

CONTRIBUTORSIan Deleón Archives

July 2023

|

|

MISSION // Based in Brooklyn, NYC, PERFORMANCE IS ALIVE is an online platform featuring the work and words of current performance art practitioners. Through interviews, reviews, artists features, sponsorship and curatorial projects, we aim to support the performance community while offering an access point to the performance curious.

Performance Is Alive is a fiscally sponsored project of Fractured Atlas, a 501(c)(3) charity. Contributions made payable to Fractured Atlas for the purposes of Performance Is Alive are tax-deductible to the extent permitted by law. |