|

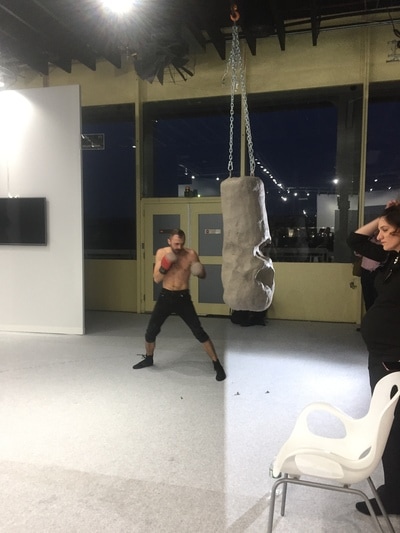

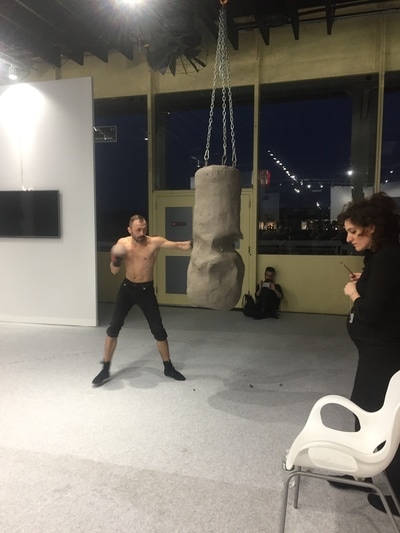

Boxing with Szilard Gaspar Zorzini Gallery at Volta Art Fair, NYC, March 1, 2017 By Alexandra Hammond As a steady stream of people breezed through the long corridors of the Volta Art fair at Pier 90, concentration gathered at booth F01, occupied by Zorzini Gallery of Bucharest, Romania. A slender young man, Romanian artist Szilard Gaspar, with the face of a saint from a Spanish Golden Age painting, arrived in the booth, seated himself and began changing his shoes and taping his hands. His preparations were executed with the specificity of a trained athlete. The intimacy of these actions was heightened by the art fair setting, where everyone’s gaze is trained to the external world of images, objects, opportunities for social networking, sales. The spectacle of the person changing from one activity to another, dressing and undressing, took on the importance that Mr. Rogers so aptly demonstrated in his children's show, where the ritual of the daily change of clothes, from outdoor jacket to cardigan, dress shoes to sneakers became a stabilizing routine and a marker of a boundary from one place and one kind of activity to the next. It was not so much a necessity, that the new activity could not be performed or inhabited without the wardrobe change, as a decision to enter a new mode of operation.

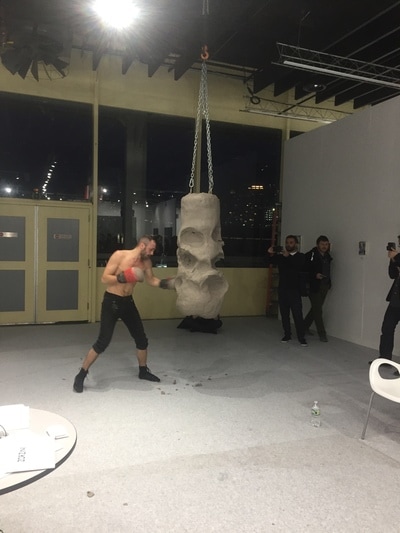

On another day, without the countless moveable walls of the art gallery booths, one could easily imagine the vast expanse of Pier 90 transformed into a massive gym or sporting arena, fitting several boxing rings with room for betting onlookers. But on a day like March 1, with the building dedicated primarily to betting on investments in art, Gaspar and his clay punching bag demonstrated why boxing is called the sweet science. With precision and grace, the lightweight pummeled the inert yet malleable body of clay, leaving deep, round, boxing-glove-shaped craters on its surface, each dent a record of the force with which the padded human fist can be thrust through the air ahead of the arm, originating from the chest and core, and ultimately grounded on the nimble feet. During brief water breaks between rounds, onlookers could contemplate the changing shape of the clay punching bag, which was taking a beating. The visceral feeling of witnessing violence was surprising to me, since the recipient of Gaspar’s punches was nothing more than a large lump of clay. But seeing the evidence of each blow transferred onto the surface of this stand-in body made it seem like a corpse or a defenseless victim of a lithe and relentless artist in his quintessential display of male dominance. In contrast to many feminist artists who have performed with this elemental material, such as Kate Gilmore’s “Through the Claw” (2011), Heather Cassils’ “Becoming an Image” (2012), and even Ana Mendieta’s “Silueta Series” body-imprint earthworks of the 1970 and ‘80s, Gaspar’s performance maintains the reflexive stance of the artist forming his sculpture, surrounded by onlookers. Instead of tearing down the small monument (as in Gilmore’s piece), highlighting the relation between viewers, images and bodies (as in Cassils’) or creating a place in the clay to fit one’s own body (as in Mendieta’s), Gaspar performs the live production of a future art object. FULL CONTACT PERFORMANCE documentation

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

CONTRIBUTORSIan Deleón Archives

July 2023

|

|

MISSION // Based in Brooklyn, NYC, PERFORMANCE IS ALIVE is an online platform featuring the work and words of current performance art practitioners. Through interviews, reviews, artists features, sponsorship and curatorial projects, we aim to support the performance community while offering an access point to the performance curious.

Performance Is Alive is a fiscally sponsored project of Fractured Atlas, a 501(c)(3) charity. Contributions made payable to Fractured Atlas for the purposes of Performance Is Alive are tax-deductible to the extent permitted by law. |